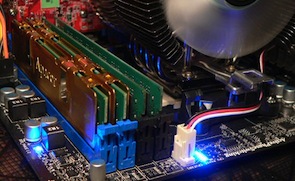

One of the more frequent questions I receive is what kind of memory allocation strategy I use in my games. The quick answer is none (at least frame to frame, I do some allocation at the beginning of each level on a stack-based allocator). This reprint of one of my Inner Product column covers quite well how I feel about memory allocation.

We’ve all had things nagging us in the back of our minds. They’re nothing we have to worry about this very instant, just something we need to do sometime in the future. Maybe that’s changing those worn tires in the car, or making an appointment with the dentist about that tooth that has been bugging you on and off.

Dynamic memory allocation is something that falls in that category for most programmers. We all know we can’t just go on allocating memory willy-nilly whenever we need it, yet we put off dealing with it until the end of the project. By that time, deadlines are piling on the pressure and it’s usually too late to make significant changes. With a little bit of forethought and pre-planning, we can avoid those problems and be confident our game is not going to run out of memory in the most inopportune moment.

On-Demand Dynamic Memory Allocation

The easiest way to get started with memory management is to allocate memory dynamically whenever you need it. This is the approach many software engineering books consider as ideal and it’s often encouraged in Computer Science classes.

The easiest way to get started with memory management is to allocate memory dynamically whenever you need it. This is the approach many software engineering books consider as ideal and it’s often encouraged in Computer Science classes.

It’s certainly an easy approach to use. Need a new animation instance when the player is landing on a ledge? Allocate it. Need a new sound when we reach the goal? Just allocate another one!

On-demand dynamic memory allocation can help to keep memory usage to a minimum, because, you only allocate the memory that you need and no more. In practice it’s not quite as neat and tidy because there can be a surprisingly large amount of overhead per allocation, which adds up if programmers become really allocation-happy.

It’s also a good way to shoot yourself in the foot.

Games don’t live inside a Computer Science textbook, so we have to deal with real world limitations, which make this approach cumbersome, clunky, and potentially disastrous. What can go wrong with on-demand dynamic memory allocation? Almost everything!

Limited Memory

Games, or any software for that matter, run on machines with limited amounts of memory. As long as you know what that limit is, and you keep extremely careful track of your memory usage, you can remain under the limit. However, since the game is allocating memory any time it needs it, there will most likely come a time when the game tries to allocate a new block but there is no memory left. What can you do then? Nothing easy I’m afraid. You can try to free an older memory block and allocate the new one there, or you can try to make your game tolerant to running out of memory. Both those solutions are very complex and difficult to implement correctly.

Even setting memory budgets and sticking to them can be very difficult. How can a designer know that a given particle system isn’t going to run out of memory? Are these AI units going to create too many pathfinding objects and crash the game? Hard to say until we run the game in all possible combinations. And even then, how do you know it isn’t going to crash five minutes later? Or ten? It’s almost impossible to know for certain.

If you insist in using this approach, at the very least, you should tag all memory allocations, so you have an idea of how memory is being used. You can either tag each allocation based on what system initiated it (physics, textures, animation, sound, AI, etc) or even on the filename where it originated, which has the advantage that it can be automated and should still give you a good picture of the overall memory usage.

Memory Fragmentation

Even if you take lots of pain not to go over your the available memory, you might still run into trouble because of memory fragmentation. You might have enough memory for a new allocation, but in the form of many small memory blocks instead of a large contiguous one. Unless you provide your own memory allocation mechanism, fragmentation is something that is very hard to track on your own, so you can’t even be ready for it until the allocation fails.

Virtual Memory

Virtual memory could solve all those problems. In theory, if you run out of real memory, the operating system swaps out some older, unused pages to disk and makes room for the new memory you requested. In practice, it’s just a bad caching scheme because it can be triggered at the worst possible moment, and it doesn’t know about what data it’s swapping out or how your game uses it.

Games, unlike most other software, have a “soft realtime” requirement: The game needs to keep updating at an acceptable interactive rate, which is somewhere around 15 or more frames per second. That means that gamers are going to make a trip to the store to return your game if it pauses for a couple of seconds every few minutes to “make some room” for new memory. So relying on virtual memory isn’t a particularly attractive solution.

Additionally, lots of games run in platforms with fixed amounts of RAM and no virtual memory. So when memory runs out, things won’t get slow and chuggy, they’ll crash hard. When the memory is gone, it’s really gone.

Performance Problems

There are some performance issues that are relatively easy to track down and fix. Usually ones that occur every frame and are happening in a single spot: some expensive operation, a O(n3) algorithm, etc. Then there are performance problems introduced by dynamic memory allocations, which can be really hard to track down.

Standard malloc returns memory pretty quickly, and usually doesn’t ever register on the the profiler. Every so often though, whenever the game has been running for a while and memory is pretty fragmented, it can spike up and cause a significant delay for just a frame. Trying to track down those spikes has caused more than one programmer to age prematurely. You can avoid some of those problems by using your own memory manager, but don’t attempt to write a generic one yourself from scratch. Instead start with some of the ones listed in the references.

Malloc spikes are not the only source of performance problems. Allocating many small blocks of memory can lead to bad cache coherence when the game code access them sequentially. This problem usually manifests itself as a general slowdown that can’t be narrowed down in the profiler. With today’s hardware of slow memory systems and deep caches, good memory access patterns are more important than ever.

Keeping Track Of Memory

Another source of problems with dynamic memory allocation are bugs in the logic that keeps track of the allocated memory blocks. If we forget to free some of them, our program will have memory leaks and has the potential to run out of memory.

The flip side of memory leaks are invalid memory access. If we free a memory block and later we access it as if it were allocated, we’ll either get a memory access exception, or we’ll manage to corrupt our own game.

Some techniques, such as reference counting and garbage collection can help keep track of memory allocations, but introduce their own complexities and overhead.

Introducing Pre-allocation

On the opposite corner of the boxing ring is the purely pre-allocated game. It excels at everything that the dynamically-allocated game is weak at, but it has a few weaknesses of its own. All in all, it’s probably a much safer approach for most games though.

The idea behind a pre-allocation memory strategy is to allocate everything once and never have to do any dynamic allocations in the middle of the game. Usually you grab as big a block of memory as you can, and then you carve it out to suit your game’s needs.

Some advantages are very clear: no performance penalties, knowing exactly how your memory is used, never running out of memory, and no memory fragmentation to worry about. There are some other more subtle advantages, such as being able to put data in contiguous areas of memory to get best cache coherency, or having blazingly-fast load times by loading a baked image of a level directly into memory.

The main drawback of pre-allocation is that is more complex to implement than the dynamic allocation approach and it takes some planning ahead.

Know Your Data

For preallocation to work, you need to know ahead of time how much of every type of data you will need in the game. That can be a daunting proposition, especially to those used to a more dynamic approach. However, with a good data baking system (see last month’s Inner Product column), you can get a global view of each level and figure out how big things need to be.

There is one important design philosophy that needs to be adopted for preallocation to work: Everything in the game has to be bounded. That shouldn’t feel too restrictive; after all, the memory in your target platform is bounded, as well as every single resource. That means that everything that can create new objects, including high-level game constructs, should operate on a fixed number of them. This might seem like an implementation detail, but it often bubbles up to what’s exposed to game designers. A common example is an enemy spawner. Instead of designing a spawner with an emission rate, it should have a fixed number of enemies it can spawn (and potentially reuse them after they’re dead).

Potentially Wasted Space

If you allocate enough data for the worst case in your game, that can lead to a lot of unused data most of the time. That’s only an issue if that unused data is preventing you from adding more content to the game. We might initially balk at the idea of having 2000 preallocated enemies when we’re only going to see 10 of them at once. But when you realize that each of those enemies is only taking 256 bytes and the total overhead is 500 KB, which can be easily accommodated in most modern platforms today.

Preallocation doesn’t have to be as draconian as it sounds though. You could relax this approach and commit to having each level preallocated and never having dynamic memory allocations while the game is running. That still allows you to dynamically allocate the memory needed for each level and keep wasted space to a minimum. Or you can take it even further and preallocate the contents of memory blocks that are streamed in memory. That way each block can be divided in the best way for that content and wasted space is kept to a minimum.

Reuse, RecycleM

If you don’t want to preallocate every single object you’ll ever use, then you can create a smaller set, and reuse them as needed. This can be a bit tricky though. First of all, it needs to be very much specific to the type of object that is reused. So particles are easy to reuse (just drop the oldest one, or the ones not in view), but might be harder with enemy units or active projectiles. It’s going to take some game knowledge of those objects to decide which ones to reuse and how to do it.

It also means that systems need to be prepared to either fail an allocation (if your current set of objects is full and you don’t want to reuse an existing one), or they need to cope with an object disappearing from one frame to another. That’s a relatively easy problem to solve by using handles or other weak references instead of direct pointers.

Then there’s the issue that reusing an object isn’t as simple as constructing a new one. You really need to make sure that when you reuse it, there’s nothing left from the object it replaced. This is easy when your objects are just plain data in a table, but can be more complicated when they’re complex C++ classes tied together with pointers. In any case, you can’t apply the Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII) pattern, but it doesn’t seem to be a pattern very well suited for games, and it’s a small price to pay for the simplicity that preallocation provides.

Specialized Heaps

Truth be told, a pure pre-allocated approach can be hard to pull off, especially with highly dynamic environments or games with user-created content. Specialized heaps is a combination of dynamic memory allocation and pre-allocation that takes the best of both worlds.

The idea behind specialized heaps is that the heaps themselves are pre-allocated, but they allow some form of specialized dynamic allocation within them. That way you avoid the problems of running out of memory, or memory fragmentation globally, but you still can perform some sort of dynamic allocation when needed.

One type of specialized heaps is based on the object type. If you can guarantee that all objects allocated in that heap are going to be of the same size, or at least a multiple of a certain size, memory management becomes much easier and less error prone, and removes a lot of the complexity of a general memory manager.

My favorite approach for games is to create specialized heaps based on the lifetime of the objects allocated in them. These heaps use sequential allocators, always allocating memory from the beginning of a memory block. When the lifetime of the objects is up, the heap is reset and allocations can start from the beginning again. The use of a simple sequential allocator bypasses all the insidious problems of general memory management: fragmentation, compaction, leaks, etc. See the code in http://gdmag.com/resources/code.htm for an implementation of a SequentialAllocator class.

The heap types most often used in games are:

- Level heap. Here you allocate all the assets and data for the level at load time. When the level is unloaded, all objects are destroyed at once. If your game makes heavy use of streaming, this can be a streaming block instead of a full level.

- Frame heap. Any temporary objects that only need to last a frame or less get allocated here, and destroyed at the end of the frame.

- Stack heap. This one is a bit different from the others. Like the other heaps, it uses a sequential allocator and objects are allocated from the beginning, but instead of destroying all objects at once, it only destroys objects up to the marker that is popped fro the stack.

What About Tools?

You can take everything I’ve written here, and (almost) completely ignore it for tools. I fall in the camp of the programmers who consider the runtime as a totally separate beast from the tools. That means that the runtime can be lean and mean and minimalistic, but I can relax and use whatever technique makes me more productive when writing tools. That means you can allocate memory any time you want, you can use complex libraries like STL and Boost, etc. Most tools are going to run on a beefy PC and a few extra allocations here and there won’t make any difference.

Be careful with performance-sensitive tools though. Tools that build assets or compute complex lighting calculations might be a bottleneck in the build process. In that case, performance becomes crucial again and you might want to be a bit more careful about memory layout and cache coherency.

On the other hand, if the tool you’re writing is not performance sensitive, you should ask yourself if it really needs to be written in C++. Maybe C# or Python are better languages if all you’re doing is transforming XML files or verifying that a file format is correct. Trading performance for ease of development is almost always a win with development tools.

Next time you reach out for a malloc inside your main loop, think about how it can fail. Maybe you can pre-allocate that memory and stop worrying about what’s going to happen the day you prepare the release candidate.

This article was originally printed in the February 2009 issue of Game Developer.

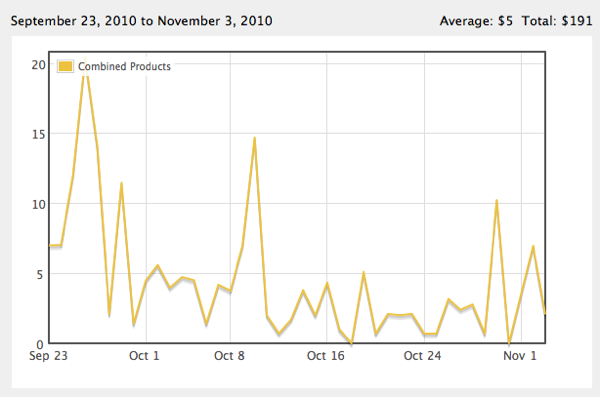

I like to be as open as possible about any project I’m working on, whether it’s giving talks, sharing technology, or discussing sales numbers. That goes for projects in progress too, although sometimes it makes sense to wait a while before announcing them. In the case of

I like to be as open as possible about any project I’m working on, whether it’s giving talks, sharing technology, or discussing sales numbers. That goes for projects in progress too, although sometimes it makes sense to wait a while before announcing them. In the case of  Both Miguel and I felt this was a very slow week. I’m not sure exactly why, but I suspect post-IGF submission syndrome. We’re feeling the mini-crunch we did leading up to it, and now we have lots of not-so-fun tasks to do on our planes. Still, I think we’ve been slowly picking up speed. Next week should be a fully productive one.

Both Miguel and I felt this was a very slow week. I’m not sure exactly why, but I suspect post-IGF submission syndrome. We’re feeling the mini-crunch we did leading up to it, and now we have lots of not-so-fun tasks to do on our planes. Still, I think we’ve been slowly picking up speed. Next week should be a fully productive one. It’s no secret that I like a good conference. Actually, I’m sure I can find something to enjoy even at a so-so conference. Each field has it’s big, ultimate conference: For games it’s

It’s no secret that I like a good conference. Actually, I’m sure I can find something to enjoy even at a so-so conference. Each field has it’s big, ultimate conference: For games it’s

The easiest way to get started with memory management is to allocate memory dynamically whenever you need it. This is the approach many software engineering books consider as ideal and it’s often encouraged in Computer Science classes.

The easiest way to get started with memory management is to allocate memory dynamically whenever you need it. This is the approach many software engineering books consider as ideal and it’s often encouraged in Computer Science classes.