Ever since I turned indie, version control just hasn’t been much of an issue. Gone are the days of hundreds of multi-GB files that changed multiple times per day. With small teams of one or two plus a few collaborators, Subversion hosted remotely worked fine. Of course, all the cool kids these days are going on about how their distributed version control systems solve world hunger, but I’ve been mostly ignoring it because I have better things to do with my time (like writing games [1]).

Yesterday things changed a bit. As a result of last week’s “growing” post, Manuel Freire is going to join me to help with Flower Garden development. That makes two of us banging on the same codebase, and from two different time zones, so we don’t get the benefit of being in the same closet as it was the case with Power of Two Games. Since I was in my get-things-done mindset, I figured I would just set up a new svn repository for the project, move over the Flower Garden data, give us both access to it, and move on.

But no, it couldn’t be that easy. Can you guess what the first words out of his mouth were when I asked him about version control? “Oh, I love Git!”

That was the last straw. I had to do a mini-research session on version control systems, so I spent a couple of hours looking into it. If we were going to move over to something, now would be the time to do it.

Git and Mercurial

Git and Mercurial both look great. I was debating which one to go with until I realized that they’re both two flavors of the same thing, so it comes down more to personal preferences and tastes. This is best description I found on the differences between Git and Mercurial. When it comes to computers, I’m totally a MacGyver guy (actually, that might be true when it comes to anything now that I think about it), so that made my decision easier.

The big feature everybody keeps talking about for distributed version systems is effortless branching. That’s great, but I really have no intention of branching much. I haven’t created a single branch in the last four years, and I don’t expect to start doing that now. Next.

The other big feature is working disconnected from the network. That’s something I could use, but considering I’m only offline a handful of times a year, it really isn’t enough of an incentive to switch to a whole new system.

Git sounds like a great tool for large, distributed, open-source projects with hundreds of contributors, but frankly, I couldn’t find anything else that was worth mentioning for a small project and a handful of people. I feel like someone is trying to sell me a Porsche when my beat-up Hyundai is still perfectly functional for driving to the grocery store once a week. Am I missing something obvious?

Hosting

Hosting the actual repository was part of the consideration. This is for a private project, so all open-source sites are out. Ideally I wanted to host it just like I do with Subversion in Dreamhost, but the instruction page on how to install Git and Mercurial are enough to put most people off. Clearly, there’s a steep learning curve there.

So I asked on Twitter for recommendations. I’ve learned that Git and Mercurial users are definitely very vocal and are always willing to help someone join their ranks. Within minutes I had all the suggestions listed below:

So I asked on Twitter for recommendations. I’ve learned that Git and Mercurial users are definitely very vocal and are always willing to help someone join their ranks. Within minutes I had all the suggestions listed below:

- Github (Git)

- Repositoryhosting.com (Git, Hg, SVN)

- Bitbucket (Hg)

- Klin (Hg)

- CodaSet (Git)

- Assembla (Git, SVN)

- Unfuddle (Git, SVN)

- Beanstalkapp.com (Git, SVN)

- SourceRepo (Git, Hg, SVN)

- Plain Dropbox (Git I guess)

- Self-hosting (gitosis for managing Git)

Prices varied a lot. From the $25/month/user of Kiln, to the $6/month of RepositoryHosting (gets you unlimited users and 2GB of storage). The Snappy Touch repository is already over 2GB, so it would end up being a bit more expensive than that, but not too bad.

Of those, Github was definitely the most recommended. I was starting to feel Git might not be the one for me, so I looked a bit more into RepositoryHosting because they had Subversion support. It turns out they also provide Trac, which is a great tool, although I already have that set up myself.

Wish List

Binary files

The one thing I really want in a version control system is good large binary file handling. I check in everything under version control, source code, assets, raw assets, and even built executables for each version. I want to be able to throw multiple GB psd files in the repository and have it work correctly (meaning fast, and using the least amount of space possible).

Perforce did an OK job with that. Git and Mercurial apparently are both horrible at it. So is Subversion, but at least it’s a tool I already know and I don’t have to spend time learning the ins and outs of how to optimize the Git database or how to make backups, or cull unused trees.

GUI

I love my command-line tools. I live in Terminal for a good part of the day, and having a real shell is one of the things that makes my life so much more pleasant under Mac OS than under Windows. But there are some things for which a GUI tool is a really useful addition, and version control is one of them.

On the Mac, I’ve been using Versions as a client for Subversion and it does everything I want. It’s fast, handles multiple repositories, lets me browse history, diff changes, etc. From my brief search and other people’s comments, there’s nothing quite like that for Git or Mercurial yet. That’s a pretty big, gaping hole.

Low-level access

Looking at all those hosting providers, I realized how much I want to have low-level access to the database. I want to be able to back it up myself, and run svnadmin when I want to. A lot of those hosting sites looked really pretty, but you were very limited in what you could do.

Coming To A Decision

If this were a thriller, you’d be disappointed. I’m afraid there are no plot twists and you can already guess the conclusion.

In the end, since neither Git nor Hg are built to address my biggest need (large binary files), I’ll stick with svn. It might be old, it might not be cool, but it serves my needs, I already know how to use it, I have the tools, I can admin it and fix a problem. I can concentrate on what matters instead: Writing games.

I decided to continue hosting it myself on Dreamhost. I can easily have one repository for every major project. However, by default, Dreamhost creates svn repositories using htaccess security and HTTP protocol. That’s OK, except that none of the actual data is encrypted as it would be if I were using ssh. I could use HTTPS, but then I would have to set up a certificate and pay for a fixed IP address, so instead I found an alternate way to have a secure connection.

All Subversion repositories live in a user account (svnuser). I create a new user group for every repository, and change all the files in the repository to belong to that group. Make sure you also set the SGID bit so any files created in that directory still belong to the group. Then I can create a new shell user for every collaborator, and add him to the groups of the repositories I’d like him to have access to. At that point, he’ll be able to access the repository as svh+ssh://username@hostname.com/home/svnuser/repository. All safe and secure.

Bonus SVN-Fu

Here’s something that I learned yesterday while I was moving repositories around. It’s probably common knowledge for seasoned SVN admins, but it was new to me.

I had a repository that included a bunch of my projects. What I wanted was to create a new repository that still had all the history, but only for the FlowerGarden part of the tree. I knew about svnadmin dump for transferring whole repositories, but I didn’t know there was a very simple way to only transfer part of it.

First you need to dump it as usual:

svnadmin dump repository > repos-dumpfile

Now, it turns out you can process the dump file before adding it back to another repository. So we can do:

svndumpfilter include FlowerGarden --drop-empty-revs --renumber-revs < repos-dumpfile > fg-dumpfile

Finally, you can add the resulting dump file into a fresh repository and have all the history for that project and only that project:

svnadmin create flowergarden svnadmin load --ignore-uuid flowergarden < fg-dumpfile

Amazingly, for a repository that was over 2GB, that only took a few minutes. Go Subversion!

[1] Or reading. Or going for a walk. Heck, even sleeping would be a better use of my time than futzing around with a new tool.[2]

[2] And yes, I realize I sound like a grumpy old man. Getting there apparently. Now get off my lawn.

This post is part of iDevBlogADay, a group of indie iPhone development blogs featuring two posts per day. You can keep up with iDevBlogADay through the web site, RSS feed, or Twitter.

The first choice is nice and safe. We can keep doing what we love, making a living from it, and even saving some money. Assuming the App Store doesn’t collapse overnight, we might be able to pull that off for a few more years. But it has a horrible hidden cost: The opportunity cost.

The first choice is nice and safe. We can keep doing what we love, making a living from it, and even saving some money. Assuming the App Store doesn’t collapse overnight, we might be able to pull that off for a few more years. But it has a horrible hidden cost: The opportunity cost.

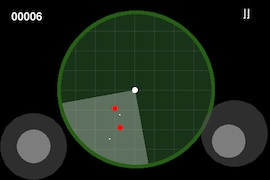

In modern hardware it’s also really easy to do with a shader, but Paul wanted to use it across any iPhone device, and the majority of them are still stuck on OpenGL ES 1.1, so fixed-function pipeline it is.

In modern hardware it’s also really easy to do with a shader, but Paul wanted to use it across any iPhone device, and the majority of them are still stuck on OpenGL ES 1.1, so fixed-function pipeline it is.

It pains me to see

It pains me to see  Every company I’ve ever worked at has done this mistake. The team hashes out a bunch of ideas, and somehow they pick one (or create it by committee). Maybe they’ll create a prototype to show something about the game, or maybe they’ll dive straight and start writing a design document and developing technology. If you’re lucky, or you have an extremely talented game director, the game that comes out of the other end might be fantastic. In most cases, it’s just a so-so idea and the team only realizes it when the first level comes together, years later, at around alpha time. At this point the choice is canning a project after spending millions of dollars, or patching it up to try to salvage something. Neither idea is particularly appealing.

Every company I’ve ever worked at has done this mistake. The team hashes out a bunch of ideas, and somehow they pick one (or create it by committee). Maybe they’ll create a prototype to show something about the game, or maybe they’ll dive straight and start writing a design document and developing technology. If you’re lucky, or you have an extremely talented game director, the game that comes out of the other end might be fantastic. In most cases, it’s just a so-so idea and the team only realizes it when the first level comes together, years later, at around alpha time. At this point the choice is canning a project after spending millions of dollars, or patching it up to try to salvage something. Neither idea is particularly appealing. With a good prototype it’s easy to see if an idea is worthwhile. If it’s not, I discard it and move on to the next one. If it has potential but it’s just so-so, I either choose to continue just a bit longer (to ask another, better question) or I shelve it back in the list of potential game ideas. Maybe at some later time, things might click in or I might have a new inspiration and the game idea might become a lot stronger.

With a good prototype it’s easy to see if an idea is worthwhile. If it’s not, I discard it and move on to the next one. If it has potential but it’s just so-so, I either choose to continue just a bit longer (to ask another, better question) or I shelve it back in the list of potential game ideas. Maybe at some later time, things might click in or I might have a new inspiration and the game idea might become a lot stronger. Also, a good question is concise and can be answered in a fairly unambiguous way. “Is this game awesome?” isn’t a good question because “awesome” is very vague. A better question might be “Can I come up with a tilt control scheme that is responsive and feels good?”. Feels good is a very subjective question, but it’s concrete enough that people can answer that pretty easily after playing your prototype for a bit.

Also, a good question is concise and can be answered in a fairly unambiguous way. “Is this game awesome?” isn’t a good question because “awesome” is very vague. A better question might be “Can I come up with a tilt control scheme that is responsive and feels good?”. Feels good is a very subjective question, but it’s concrete enough that people can answer that pretty easily after playing your prototype for a bit. One of the key concepts in the definition of a prototype was that it has to be fast/cheap (which are two sides of the same coin). What’s fast enough? It depends on the length of the project itself. It’s not the same thing to do a prototype for a two-month iPhone game, than for a three-year console game. Also, a larger, more expensive project probably has more complex questions to answer with a prototype than a simple iPhone game.

One of the key concepts in the definition of a prototype was that it has to be fast/cheap (which are two sides of the same coin). What’s fast enough? It depends on the length of the project itself. It’s not the same thing to do a prototype for a two-month iPhone game, than for a three-year console game. Also, a larger, more expensive project probably has more complex questions to answer with a prototype than a simple iPhone game. When you’re making a prototype, if you ever find yourself working on something that isn’t directly moving your forward, stop right there. As programmers, we have a tendency to try to generalize our code, and make it elegant and be able to handle every situation. We find that an itch terribly hard not scratch, but we need to learn how. It took me many years to realize that it’s not about the code, it’s about the game you ship in the end.

When you’re making a prototype, if you ever find yourself working on something that isn’t directly moving your forward, stop right there. As programmers, we have a tendency to try to generalize our code, and make it elegant and be able to handle every situation. We find that an itch terribly hard not scratch, but we need to learn how. It took me many years to realize that it’s not about the code, it’s about the game you ship in the end.