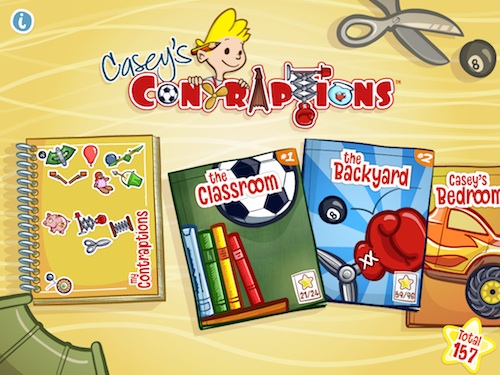

Casey’s Contraptions will be available in the US in a few hours! For those of you living in other parts of the world, it’s probably already available on your App Store. Go get it!

For the rest of you still twiddling your thumbs, eagerly awaiting for midnight, here’s some insight on what went on in the level creation for Casey’s Contraptions.

Built-in editor

From the beginning of the project, the idea was to have a level editor built in to the game. The level editor was the very first thing I implemented in the game. Before there were menus, or levels, or anything else, the game was a level editor without any goals.

That’s what Miguel and I used to create all the levels we shipped with. Nothing like eating your own dog food to make something solid and usable. This is the final level editor that players can use to create their own contraptions from scratch and send them to friends.

The only difference is that user-created levels only have the goal of getting the 3 stars in the level, whereas game levels have a separate goal. This was mostly because of the UI work required to allow the user to set different goals affecting multiple objects. It would have been way too complicated, although we’re not ruling out the possibility of extending it in the future. Miguel and I had to edit level files by hand to add the extra goal information.

Levels. Evolved.

One thing that worked really well in Casey’s Contraptions is that we had a working level editor from day one. The first prototype was a tiny level editor! Of course, we’ve been refining it since then, but the core was there.

After a month or two of development, we implement some goals and the ability to play through the levels created. That means we’ve been able to make, play, and test levels for 6 months before shipping.

It was having that amount of time to create levels that allowed the level creation to mature and let us discover what went into a fun level, to refine the difficulty, and create much more interesting levels in the end. Some of that was influenced by what mechanics were fun and which ones weren’t (placing something in a pixel-perfect position).

The different game items also had a huge influence over the level design. Clearly their functionality is going to affect level design hugely, but the surprise was that the character of the items also influenced level design quite a bit.

For example, early on, most of the levels were about solving everyday tasks Casey had to deal with: put toys away, knock down a ball from the roof, pop a balloon, etc. But as soon as we started adding some of the more colorful items, like the doll, the piggy bank, or the RC truck, our levels shifted into being mini-stories: The doll is jumping from a building and you need to catch her, the piggie is being taken away on the truck, etc. That’s when we realized that we could make really fun levels based on playtime stories, not just real situations. Probably about a third of the shipping levels are playtime levels.

Creation process

Initially, we just created levels without thinking too much about it. Used whatever items we wanted and created something that seemed fun. We were learning a lot by doing that: Playing with item interactions, seeing what was possible and what wasn’t, which items we were gravitating towards and which ones were no fun to play with. We weren’t doing it consciously, but what we really doing was exploring the possibilities of the “level space”.

As you can imagine, most of what we created early on went out of the window pretty quickly. Most of the levels were insanely difficult, and a lot of them were simply no fun at all. We were also creating the levels to challenge each other to solve them, and while that was really fun, a lot of those levels were devilishly difficult. We’ve been dialing back the difficulty level ever since then.

The actual process for creating a level wasn’t very involved. Either one of us would go ahead and create a first pass at a level. Sometimes I would sit down and consciously decide to create a new level (especially if it was a level designed to teach about a new item), but more often than not, an idea would come up while doing something unrelated in the game.

Once we had this first pass, we would send it over to the other person and have them either poke holes on the design (if the level can be solved trivially by just dropping a ball somewhere for example), or tweak it to tighten it and make it more fun. Later on, we would revisit levels based on tester feedback or us becoming more experienced.

I estimate that the average time to create a level, from the first item added to the time it was added to the game, was about half an hour. Some of them were much faster, and some much slower though. And for yet some others, we struggled with them for a whole day and finally dropped the idea completely.

What makes a good level

As we quickly learned, making a cool-looking contraption and removing a few pieces does not a good level make.

The best levels always have multiple solutions. Otherwise, it becomes a game of “guess what the designer had in mind”. There are plenty of games like that out there (and I hate them all when I feel that it turns into that). So even if we started with a complete contraption, we would always make sure there were at least two different ways of accomplishing the goals.

The other thing to avoid in a level is the possibility of trivial solutions. If a level can be accomplished by placing a single item that drops and causes the goal to complete, that’s not very fun. It was a tough balance between leaving enough freedom to create your own solutions, but making it so there were no really “cheap” and boring ones.

The stars were tricky. Each level has thee stars you can get, but they’re completely optional. Initially I wanted our levels to be easy to solve, but each star was progressively more difficult to get. Getting the third star required some serious thinking. My reasoning was that people would solve the levels first, get comfortable with the game, and then come back and get three stars in everything. Boy, was I wrong! It was clear right away that most people wanted (no, expected!) to get all three stars in their first pass through the game. So we changed most of the levels so getting the stars is not hugely difficult, especially in the early levels.

Letting the testers loose on the game was an extremely valuable experience. Not only did they catch a fair share of bugs, but they also had a fresh perspective on the game. It was amazing seeing them solve levels in totally different ways than we had anticipated. It was extremely rewarding to see people come up with solutions and even interactions I had never considered even though I had written all the code.

Here’s a good example (Spoiler alert. Skip ahead to the next section if you don’t want to learn multiple solution to one level).

Here’s one level I designed called “Angry Doll” (any references to popular iOS games must be purely coincidence, by the way 🙂

This was a level intended to highlight the use of the slingshot, but you already had the doll and one slingshot in place (and the doll misses the pig with its initial flying kick). One possible solution I had in mind was to use the remaining balls and slingshots to alter the course of the doll and knock the pig down.

There are a few different ways you can do that, which made it an interesting level. However, I was totally unprepared for some of the solutions the testers came up with.

This solution uses multiple slingshots on the doll, which changes its course and adds a lot more force to it. It flies straight for the pig and smashes it on impact. Not just that, but for extra style points, the tennis balls go flying out on a totally chaotic pattern, and they get all the stars!!

This other solution might be my favorite. It completely bypasses even the intermediate goal (alter the doll’s trajectory) and instead attaches a slingshot directly on the piggie bank and smashes it against the wall (getting a star along the way). Genius!

Item sequence

There was one additional constraint to making levels that we didn’t start dealing with until fairly late in the project: Item sequence. Initially, only a few, simple items are available to solve the goals in each level. As you play your way through the game, we introduce new items slowly, making sure their properties are well understood before introducing a new one.

The first time you complete a level with a new item, you’re “awarded” that item, and you can start using it in your own contraptions in the level editor. You can even see the stickers of the items you’ve earned so far on the cover of the “My Contraptions” book (I was playing Psychonauts at the time, so I suspect that might have influenced that design decision a bit).

Having a set item sequence meant we had to be very careful which items were available in which level. We kept a spreadsheet with all the levels, and which items were introduced when. Every new item we introduce follows the following steps:

- When an item first appears, it’s already placed in the level. That means the player gets to see how that item behaves.

- The next level, we give that item to the player so he or she can place it in the level to solve the contraption.

- Another level or two making use of that item. That reinforces the behavior of the item and makes the player comfortable with it before moving on.

We were shooting for fewer levels, but it’s not hard to see why we ended up with 72 levels in the first version of the game.

To be really sure we were respecting the right item sequence, we even wrote a script that parsed all the level files in order and spit out where each item was used. It even made sure that every item followed the rules above (first placed in the world, then available to place by the player). This will continue being extremely useful as we add more items and levels in future updates.

Make your own

There you go. That should give you an idea of what was involved in creating the levels for Casey’s Contraptions. In the near future we’re planning on holding contraption-creation contests and we hope to highlight some player-created contraptions. Go ahead and buy the game and start practicing to make your own contraptions. Remember: The crazier the better!

No, this is not an announcement of my next game (I wish). Rather, it’s a brain dump of my struggle with the process. It seems that in the game development community we often share the process of making a game and how it did afterwards. But it’s rare having some insight into what goes on before the project gets started. Where do ideas come from? Why do we pick one and not another? These are semi-coherent notes about the things I’m struggling with right now.

No, this is not an announcement of my next game (I wish). Rather, it’s a brain dump of my struggle with the process. It seems that in the game development community we often share the process of making a game and how it did afterwards. But it’s rare having some insight into what goes on before the project gets started. Where do ideas come from? Why do we pick one and not another? These are semi-coherent notes about the things I’m struggling with right now.